The labor shortage has many restaurants in a pickle. Finding employees is hard, retaining them is harder still. A solution may be as close as the nearest culinary training program, where people already excited about food could emerge as a new generation of foodservice professionals.

“It’s our job to train potential employees for the industry,” said Chef Werner Absenger, Director of the Secchia Institute for Culinary Education at Grand Rapids Community College (GRCC) in Michigan. “But it doesn’t stop there … how do we make the industry sexy for those students?”

The answer: training. A number of experts echo this point, stressing that culinary programs can feed the desire for restaurant careers, but they won’t relieve labor shortages and high turnover alone. The key to hiring and keeping employees is engagement and growth opportunities.

Representatives from a middle school program, a high school ProStart program, a culinary school, and a work-release program all weighed in on culinary training and what comes next.

Starting young—a middle school perspective

Restaurant work is a first job for many young people. Common hopping on points include bussing tables, washing dishes or taking orders. It’s not glamorous, and doesn’t appeal for long to kids with dreams of becoming a celebrity chef.

“You just can’t pile responsibilities on 16-year-olds without giving them enough training,” Holly Newman said. She’s a family and consumer sciences educator who teaches a seventh-grade class at Kennedy Middle School in Rockledge, Florida.

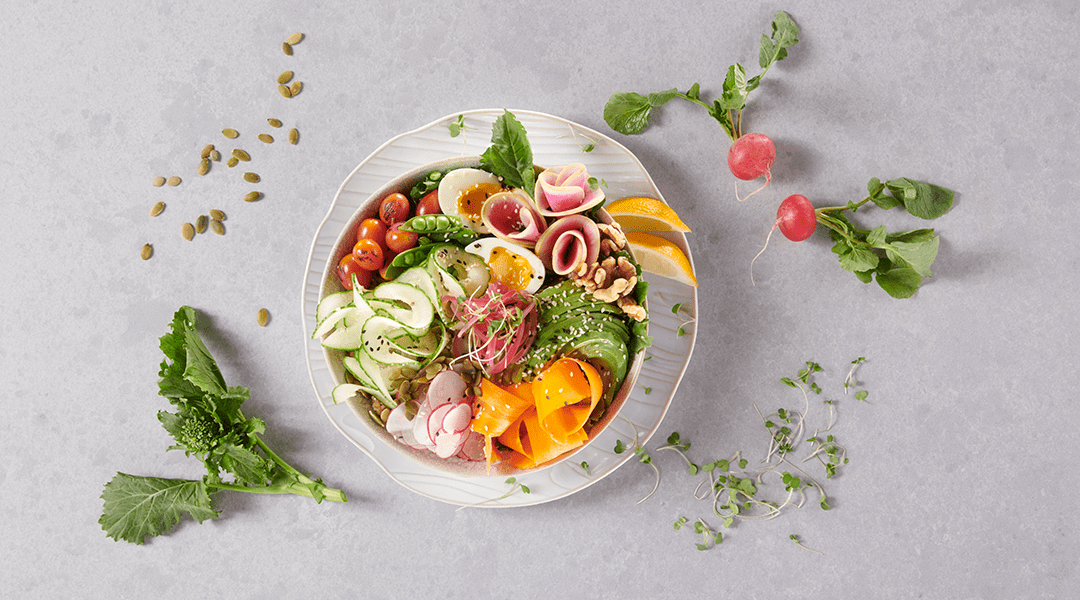

Students enter her program because they like food. They quickly learn food is a business with many career avenues. Newman’s class is an elevated home-economics program, where she stresses food safety, food costs, portion control and restaurant service. “By the end of the year, we set up the classroom like a restaurant with kids in the front of the house taking orders and kids in the back of the house running the kitchen,” she said.

As a former hospitality worker and now a 22-year teacher working with middle schoolers, she has advice to operators dealing with today’s youngest workers: Have patience and be tolerant.

“If all you did was ask them to watch a video, then write them up for making one simple mistake, I have a problem with that,” she said. “It takes many opportunities and second chances for them to learn, but they will get it if you give them enough training.”

The next step—the high school perspective

For restaurant operators dealing with every facet of business, training is time consuming. That puts a program like ProStart in a position to prepare high-schoolers so restaurants can show them a career path.

ProStart is a two-year program developed by the National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation that reaches about 130,000 students in high schools nationwide. For Alex Vernon, his own high school involvement led him to a career as ProStart Program Manager of the Wisconsin Restaurant Association Education Foundation. He oversees Wisconsin’s ProStart training and education, which focuses on “The Three C’s”—curriculum, competition, and careers.

Curriculum. With textbooks and course work, ProStart acts similarly to an advanced placement (AP) food course.

Competition. ProStart holds a statewide competition where students are judged on everything from kitchen basics to cooking skills to management knowledge. Statewide winners advance to a national competition.

Careers. The ultimate goal is to open students’ eyes to the many career sectors that await—distribution, manufacturing, restaurant, hotel lodging, golf course, food styling, etc.

“ProStart allows us to introduce high school students to the wide range of hospitality career paths and opportunities,” said Connie Fedor, Executive Director for the Wisconsin Restaurant Association Education Foundation. “I think perception is the industry’s No. 1 obstacle … people don’t see hospitality as a viable career path.”

What starts with culinary education culminates with operators finding ways to become preferred employers, whether it’s with higher wages, work-life balance or providing training that opens advancement. “Even if people love to cook or love the business, they will leave a bad manager,” she said.

Higher ed—a culinary school perspective

At the college level, GRCC’s Absenger works with students financially invested in the culinary field. They choose from an associate’s degree program in Culinary Arts or Pre-Major Hospitality Management, and can enroll to earn certificates in Baking and Pastry, Craft Brewing, Culinary Arts and Personal Chef.

The goal of any of GRCC’s programs is for graduates to have a skill set that requires minimal on-the-job training to become productive employees.

“If we do our job and make sure students stick with the program, then the industry will be kind to them and help them figure out what to do afterwards,” he said. “Our goal is not to produce executive chefs right off the bat, that’s not realistic.”

For operators seeking to limit turnover, Absenger points out that employees are more likely to stay when they know the possibilities that await.

“People starting out need to know they may never become an executive chef in a mom and pop restaurant, but if you start small at a major corporation, you can grow from a line cook to a supervisor to a sous chef to an executive chef—it could be a career that lasts your whole life,” he said. “Sometimes employers fail to stress the potential.”

Cultivating talent starts right away, Absenger said. It takes effort on the operator’s part to notice a dishwasher who has the desire to be a supervisor. That’s when mentoring starts and doors open to new roles or even a new location at an affiliate restaurant.

Second chances—an alternative perspective

The search for qualified restaurant employees is tough, and freshly minted culinary school graduates aren’t the only answer. At the SMA Healthcare Reality House in Daytona Beach, Florida, a work-release program that’s part of SMA Healthcare and helps prison inmates get back on their feet with foodservice education.

“While I was working with inmates, the realization came to me that before they got in trouble, a lot of these people worked in restaurants,” said Kirk Kief, CEC, CCA, CPC, Director, Food Service Operations at the transitional living center. “I used to teach a culinary program that culminated with ACF certification.”

When budget cuts hit, his successful program was scaled back, and he now teaches a Food Safety Manager course.

“I only have them for a week and they have to go out and find a job or go back to prison, so I teach them a food safety manager course because that’s a good card for them to have,” Kief said, referring to the Certified Food Manager qualification. A certificate demonstrates understanding of safe storage, preparation and serving of food—a basic skill set for starting out in the food business.

Kief understands the skills employees need. His kitchen prepares more than 1,200 meals a day at six programs. Kief also understands what it means to start anew. After spending years as a photographer, he turned to culinary school at age 51. Now, 20 years later, he’s an American Culinary Federation Certified Executive Chef who appreciates the value training brings.

“Does [culinary education] help reduce turnover? Of course it does,” he said. “If you know what you’re getting into, you’re going to stay with it a lot longer.”