In Texas, it all began with strawberries—1.5 million plants, so history tells us. After towns near Galveston were devastated by a hurricane in September 1900, Red Cross founder Clara Barton provided strawberries to help farmers recover. With only half a growing season remaining and much of the topsoil washed away, quick-to-establish strawberries provided relief.

Strawberries have been part of the Texas agricultural landscape ever since. More than a century later, strawberries were the plant Susan LeBlanc tried first when she started a school garden program at Barbers Hill Independent School District east of Houston. It began partly as a history lesson and a way to explain the origins of popular smoothie and ice cream flavors.

The school garden program blossomed from a few strawberry plants and now includes five gardens—three that LeBlanc manages with 400 second-graders and two other elementary school gardens that are part of a junior master gardener program.

“I knew zip about how to build a garden program and teach lessons, but the a-ha moment was when each child knew which strawberry plant was theirs,” the district’s 25-year Director of School Nutrition says about the excitement generated by that first garden. Now the students take pride in growing broccoli, spinach, carrots, lettuce, cauliflower and other vegetables that thrive in the fall.

Sowing the farm-to-school garden seeds

Recognizing the vital role farming and food play is the driving force behind garden programs at schools in diverse settings, from rural areas to coastal communities to large urban settings. Part of the credit goes to the 2010 Congressional approval of October as National Farm to School Month, calling on school meal programs to improve child nutrition, support local economies and educate about food.

With space limitations, time commitments and food-safety regulations to consider, schools are unable to grow all the food to supply cafeteria needs. But surveys show farm-to-school programs increase school lunch participation by as much as 16 percent, driven by such things as visits to farms and gardening activities.

Nowhere is the connection more evident than at Sarasota County Schools in Florida, where Director of Food and Nutrition Services Beverly Girard says there are more than 40 school gardens at all grade levels. She calls the school plots “demonstration gardens,” where students and teachers grow food and study nutrition, science and math. They only produce enough for students to sample some of the goodness, but it’s enough to promote a love of fresh, homegrown food and an interest in nutrition.

“We have everything from pizza gardens [think tomatoes and peppers] to food forests [mangoes and other trees] to herb boxes outside the door to the main office,” she says. “When the kids start to harvest, they can’t wait to try it—it builds acceptance and consumption.”

Interest in gardening is due in part to the district’s Farm to School Program. In 2013, Sarasota received a $100,000 USDA grant allowing Girard to add to an existing program by reaching out to Florida farmers to fill menu needs. Today, the district receives 62 percent of its vegetables from state farmers.

The district also added a Farm to School Coordinator, Zach Gloriosso, who came to the school from the Florida Institute of Agricultural Science. He supports the school gardens as well as coordinates farm partnerships that have expanded menus. He and Girard work with farmers—potato, corn, tomato and bean growers, dairy farmers and, recently, beef ranchers—to procure some of the district’s food. For the students, it allows them to visit farms and understand the work involved.

“Our aim is to take what we learn and build a passion that leads to a potential career,” Girard says. For the schools, her dream is to have at least three fully functioning production farms run by students, providing foods such as oranges, avocados and tomatoes. “We live in a veritable Garden of Eden during the growing season.”

Taking it to the streets

The flip side of Florida’s fertile environment is the big city, but that doesn’t stop the students at Chicago’s Gary Comer Youth Center from being productive gardeners. Garden Manager Marji Hess said students at the urban campus grew more than 20,000 pounds of produce in 2016.

The school has two gardens and two unheated greenhouses. The school’s rooftop garden grows about 1,000 pounds of food that’s mostly used by the youth center’s garden and culinary programs. The street-level garden, a 1.75-acre organic growing area across the street in what once was a brownfield area, grows strawberries, apples, asparagus, beans, corn, squash and more. The greenhouses are used primarily for season-extending crops such as spinach and lettuce and heat-loving crops such as tomatoes and peppers.

“We keep 80 percent of what we grow in the community,” Hess says. “We donate a lot to food pantries and shelters, and in the summer we have a salad bar and a farmers market with food grown by students who commit to working 12 hours a week.”

Very little of what’s grown is used for lunches, but some of the food is used for after-school snacks. Mostly what students get out of the garden program is an education. The 200 students in the Green Teen Program learn job readiness—and a small paycheck—using knowledge they gain from gardening to work and explore careers in farming, agricultural science and culinary fields.

“Gardening provides a lot education opportunities,” Hess says. “Not only is there soil testing and learning about the environment, but it’s a stepping stone to global issues.”

The students also learn healthy eating habits, evident on a school trip to Yellowstone National Park. Hess said students practiced what they learned in the gardens by preparing lots of healthy salads and enjoying the ultimate fast food—fruit—during their wilderness adventure.

A big-picture connection

At Shoreline Elementary School in Michigan’s Whitehall District Schools, the garden program is a big hit. Lynn DeVlieg, who created the program as a volunteer now runs it as the Farm-to-School Coordinator funded by grant money, directs a 1,280-square-foot fenced-in garden at the school. A little less than half of that area is currently planted.

“We do taste tests in the garden as much as possible, but we don’t grow enough to supply the lunchroom, so we have to explain the connection between what we grow and what we eat,” DeVlieg says. “When a boy planting pea seeds asked me if the same pea he eats can be planted in the soil to grow a new plant, I was able to explain that food growers and eaters are all part of the same system.”

The more involved students get, the more they want to try the foods they grow, DeVlieg says. And while they are gardening, they also learn how worms and bugs benefit the soil, get an understanding of composting, and even learn math by figuring out how much can be planted per square foot.

Beyond food, every garden has something in common. That’s the buy-in from students, teachers, foodservice directors and administrators, as well as a lot of help from parents and community volunteers. “I couldn’t do it without them, or without a fence to keep out the deer,” DeVlieg says.

Hard work is a way of life for farmers, and school gardens also involve a lot of sweat, but for four schools in diverse settings and vastly different climates, it has been worthwhile.

“Young people are fascinated by nature,” Chicago’s Hess says. “It helps for gardeners to share what they know, and trust that young people will take it to good places.”

Planting the seeds for school garden growth

School garden managers offer their advice on what’s needed to start a program:

Find the right people. Because gardens aren’t initially part of most curriculum plans, parent volunteers or teachers willing to commit time during planning or lunch hour are essential.

Look for funding. Grant money may be available. Sometimes local hospitals, garden clubs or farm organizations can provide support for planting, equipment and staffing.

Seek support. Get the administration to promote it in school bulletins, and get teachers to plan lessons—environmental science, nutrition, even math—around garden activities. Talks from local chefs are a great way to make the farm to table connection.

Secure space. Not all schools have lawn space or places where there’s adequate sunlight. Consider a raised bed in an unused part of the parking lot. Think about fencing if animals are a problem.

Plan Your planting. The growing season will determine what you grow. Make sure the food can be harvested while classes are in session.

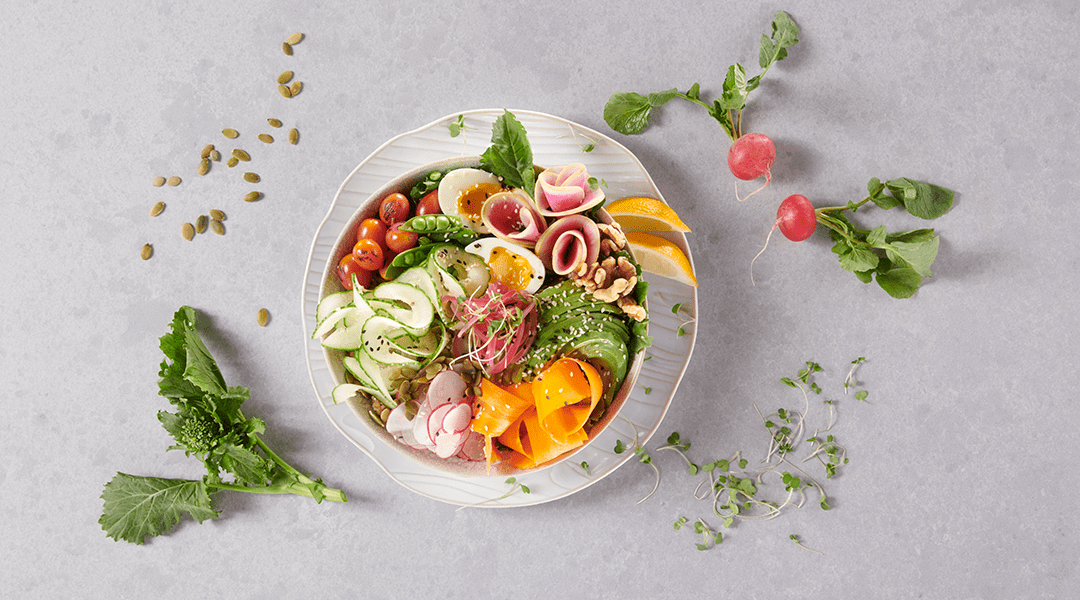

Put a fork in it. For students, the payoff is tasting the fruits and vegetables of their labor. Schedule a classroom tasting, serve the food as a snack, or make a recipe with fresh ingredients.